|

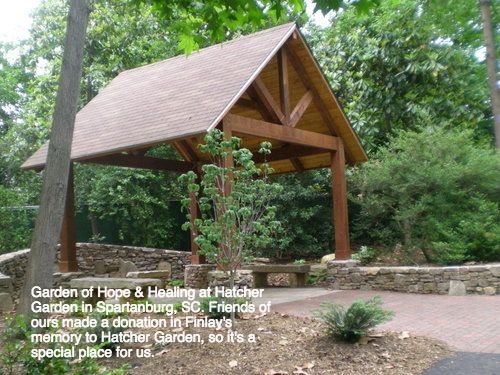

5/23/2019 0 Comments The Task of NothingIn Second Grade, I (Will) remember having an afternoon class with a teacher I had never seen before. Even though it was 30 years ago, the experience of that day sticks with me. I can think of three reasons for this. First, the teacher guided us through a hands-on exercise intended to engage our senses. We passed spices and various liquids (like vanilla extract) around a circle and tried to guess what they were by smelling, tasting, and touching them. I volunteered to taste what turned out to be garlic powder, and the teacher was impressed that I could name what it was. I was less impressed with the taste in my mouth, but quite interested in the exercise. The engagement of all of my senses left an indelible mark on my memory. Second, this was the first male teacher I had ever seen. Not only had all my previous teachers been women (in school, swim lessons, gymnastics, and other venues), but I had never even seen a male teacher in our school. Men could be teachers! Clearly, this realization stuck with me and informed, to some degree, my path in life. Third, I remember vividly a meditation that ended the class. Our teacher asked us to close our eyes and visualize various things. The final thing was “nothing.” “Now think of nothing,” he said. “Try as hard as you can. Can you do it?” I opened my eyes and looked directly at him from my place in the back of the room. I said quietly, “It’s not possible. You can’t think of nothing.” But as I looked around the class, all the other students seemed immersed in the task. They nodded their heads in assent of his question: they were all picturing nothing. When I looked back to the teacher, he met my gaze and smiled. Can you think about nothing? I’ve thought about that question since that day in 1988. This post is about nothing. While not strictly equal with death, “nothingness” provides a commensurate challenge. Nothing and death are equally gigantic in scale. How do we think of it? Why would we think of it? To think of one’s death is to prepare for and to become more intimate with one’s own finitude. There are multiple benefits to thinking of death often, not least of which is the overcoming of fear and the ability to sense new threads connecting me with my loved ones who have died. Similarly, to think of nothingness is to press the mind to its limit and expand our cognitive maps of the universe. If welcoming thoughts of death into our daily consciousness can demystify the great equalizer that so many people work feverishly to avoid, then coming to grips with nothing can throw the wild variety of our being into relief and perhaps help us to engage with the Great Mystery. This kind of activity might seem abstract and unnecessary. My hope, however, is that I can reveal some of the mind-expanding potential bound up with the task of thinking nothing, and, furthermore, to demonstrate how thinking nothingness is helpful for imagining new forms of connection with dead friends and family. I emphasize the word “task” because, like so many words, it carries a fascinating history that, once unpacked, makes the word available for new uses. After tarrying with “nothing,” I’ll move on to “task” so as to end this reflection with some specific suggestions about how the task of (thinking) nothing deepens our relations with our dead friends and loved ones. I’ve thought about nothing a lot, and I can easily summarize my findings. Nothing cannot be. There can be no nothing. Nothing, were it to have qualities (which it can’t), would need to be free from anything that has ever been. Thus, even if the universe was extinguished this very moment, it still would once have been, and therefore the remaining absence would flummox nothingness. You can’t have an absence because an absence is something, so even an absent universe is not quite nothing. Amusingly, the only way to get close to nothingness is to say that it doesn’t exist. There is no nothing. But even here, the laugh echoes back upon us since attributing any kind of is-ness to nothing ends up undoing nothing (by giving it something, a weird kind of is-ness). Nothing, it seems to me, is a relative construct, something we rely upon to distinguish between the presence and absence of things. When it comes to the grand Nothing, however, we are bound always to find something posing as nothing. French philosopher and novelist Tristan Garcia wrestles with this problem in his carefully crafted book Form et objet. He concludes: “Therefore, there is no nothing except from one of these three angles: a nothing which is in fact something; a nothing which is in fact the opposite of something [which for him means something’s form]; or a nothing which is in fact an absence of something (an emptiness or an exile). Each way leads to something, with none of them leading to a nothing” (Garcia, Form and Object 49). His point, which is also my point, a point that deserves repeating, is that nothing is something, and, therefore, it has the potential to generate ideas, affections, activities, and events. We can make something with nothing. (To read about nothing’s counterpart—Everything—click through to the parallel post, “What about Everything?”) I have had the opportunity to make something out of that which first appeared to be nothing. When Joanne and I left the hospital after Finlay’s inexplicable death during childbirth, we were overwhelmingly aware of the wrongness that was unfolding. You simply don’t leave the maternity wing with nothing. You leave with a child, as was demonstrated by all the other happy parents around us. Or not. We had, or so it seemed, discovered a loophole in the order of things. We left with nothing and commenced our life as parents whose child was dead. Except we didn’t leave with nothing. Though it would take me several months to understand, and years to put into words, I eventually realized that we left the hospital that day with something. It wasn’t the thing we wanted. In fact, it was something we absolutely didn’t want. But it was something nonetheless. We left with an unbreakable connection between the land of the living and the land of the dead. We had forged a connection with all that lay beyond the realm of the visible and knowable. In a recent podcast episode, I interviewed David Harradine and Sam Butler, the artistic directors of the English art group Fevered Sleep (Episode 6 of “To Grieve”). At the end of the interview, I asked David and Sam what it meant “to grieve.” David’s answer was precisely aligned with my thoughts on nothing (which is really something). He said (I’m paraphrasing): To grieve means to build relationships with people who are no longer here. It may seem quite difficult, since the living party is going to put in 100% of the work, but the relationship with your deceased loved one continues. Grieving is the activity of nurturing this new, non-traditional, painful/praise-worthy/depressing/joyous connection with the dead. My connection with Finlay is forged through my daily grief for his absence. What appeared at first as his nothingness when we left the hospital without him, his sheer lack of existing upon the “sterile promontory” (as Hamlet says) of my daily terrain, turned out to be his invitation to me to think beyond the limits of the ordinary. His nothing is really quite something. But the burden of it. The tax Finlay’s absence withdraws from me. To ignore the difficulty of this relationship with the dead is to gloss over a major aspect of the grief-nothingness equation. And this brings me to the task of nothingness. The history of the word reveals a connection with the Modern French word tâche, which means “duty, tax,” and this leads back into the Latin vernacular where we find tasca, “a duty, assessment.” By the late 16th century, the word (in English and French) acquires the general meaning of “any piece of work that has to be done.” This brief etymological foray provides me with a few insights. I might think of the effort required to establish an intimate bond with my dead son as a kind of tax that comes hand in hand with the wider work of conscious expansion. Among the death, dying, and grief community here in Asheville (and I suspect elsewhere in the United States), the work of reckoning with death is considered a privilege held by those for whom grief has bestowed a more nuanced understanding of death and dying. To die, I aver, is to change into a state of which we know quite little. We do know, however, that it is not an end. Death cannot lead to nothing, since, as I’ve already mentioned, there is no nothing. If death becomes, in this way of thinking, a portal to some unknown territory, then the living may find ways to communicate across the portal. To do so may mean risking one’s appearance of sanity or one’s lazy harmony with the status quo, but this risk is simply another word for the tax, or task, of making something of what first appears to be the nothing of the dead. More profound is the general meaning assigned to “task” of “any piece of work that has to be done.” In this formulation, the task of nothingness, of forging meaningful and tangible relationships with the dead, joins the ranks of our daily chores. Wake up, brush my teeth, bond with my dead son, throw my two-year-old son’s Phalen’s cloth diapers in the laundry, make coffee, imagine Finlay’s favorite breakfast food, make breakfast, etc., etc., etc. As complex as this discussion of “nothingness” and grief may seem, the result of all this philosophical labor is merely another handful of moments in the day. One of the biggest challenges faced by grief workers is to spread the wisdom that grief and death and dying ought to be as banal as buying coffee, shopping for groceries, and getting gas. Grief, and the task of nothingness, is and should be a common occurrence into which we invest as much energy as is stored in our love for those who have died. We come back to this work whenever we can, each day, and then we do the laundry. Can you think about nothing? Of course. And if you experience a profound loss—either of a person or a version of reality that you hold dear—then you’ll likely experience the visceral feeling of a gigantic hole right in the center of your universe. But this hole is not nothing. It may in fact turn out to be the Whole. Whatever it is, it is certainly something, and I think it is worth the effort to consider what we might make with this peculiar entity.

0 Comments

5/23/2019 0 Comments What about Everything?If you clicked here from my post “The Task of Nothing,” then it might make sense to jump right in: What’s the deal with Nothing’s counterpart, Everything? We’ll get there soon, I promise.

First, however, if you arrived here without first encountering my post on Nothing, then what you need to know is that I’ve thought about Nothing since I was seven years old. By the time I was 18, I had stumbled onto the realization that, in casual conversation and philosophical texts alike, Nothing tends to travel alongside Everything. I was so taken with the Zen Buddhist contemplation of Mu (Japanese for “not have; without,” written as 無) and its travelling partner Yu (“to exist; to have,” written as 有) that I got the symbols tattooed on my lower back (i.e., my center, but a place that I can’t see; an invisible everything). Traveling with Everything and Nothing has convinced me that the latter is in fact quite something. But in this post, my consideration is Everything. Specifically, it seems reasonable to suggest that if Nothing is in fact something, then something must be amiss with Everything. How are we to think of Everything? Is it one thing? Do all things retain their collective multiplicity when collected into this one Everything? If not, then was there ever a multiplicity of things to begin with, or is the appearance of multiplicity actually an illusion behind which throbs the One (whatever that might be)? I think it makes sense to provide two opposing viewpoints in order to glimpse the continuum of possible answers to these questions. One viewpoint comes from popular culture and the other from advanced mathematics. Any apparent disparity between pop culture and complex math fades away alongside the promise of Everything, which, after all, should accommodate the comparison of each thing residing in the great One (again, whatever that may be). The first viewpoint—which, I admit, I find refreshing but ultimately misleading—comes from the musical group They Might be Giants. On their 2008 children’s album, Here Come the 123s, the band sings the following words on the song “One Everything” (which, funnily enough, is song number 2 on the album. Zero comes first…that’s a different story altogether): There’s only one everything Remember these words There’s only one everything And if you go out and count up everything It all adds up to one There’s only one everything The last time I checked There’s only one everything It kinda makes sense that there would only be Just one, not ten, not three If you get all the stuff together And you have not left something out Then could there still be anything left over? I'm pretty sure that means there could not The claim here—presented as a humorous but also philosophically rich introduction to the number 1—is that Everything = 1. The great 1 of the universe shows itself if we try to imagine all things gathered together. Fascinatingly, then, Everything is not infinite or another word for infinity; it is, rather, a unity. The unity. While the band doesn’t delve into particulars, their lyrics do hint at answers to some of the big questions I asked at the beginning of this post. For example: What happens to multiplicity within this unity? They Might Be Giants suggests that the two—multiplicity and unity—co-exist in an unresolved mystery. This mystery is similar to the one that children likely feel when they ask their parents a question and receive the answer, “Because I said so.” Is that really an answer? There must be more to it. Will I ever find out??? (In their characteristic, self-reflexive lyrics, the band even acknowledges this: “There’s only one Omniverse. Go clean your room. There’s only one Omniverse.” Here, the lead singer, a father, creates a joke by juxtaposing a deep thought about the Universe/Multiverse/Omniverse and the most mundane and tedious of all parental commands, thereby underlining the co-existence of multiple strata of being within the unity of Being.) I both agree and disagree with They Might Be Giants. I quite like their tacit insistence that the One everything contains multiplicity (audible in the command to go and remove the many toys from your room’s floor, preferably while thinking about the Oneness of Everything). The wiggle room made available to the listener allows for “One” to mean something different than it usually does. Something mysterious resides in the quantity of the One. But I disagree with the quick take-away message made possible by the pithy title “One Everything.” The disagreement comes from my belief that there are many everythings, which, in turn, comes from years thinking about the work of the mathematician Georg Cantor who developed what we now call Set Theory. With this turn, I highly recommend the book Everything and More: a compact history of ∞, by David Foster Wallace, which provides a fantastic primer to the work of Cantor. Without delving into the details here, however, I can summarize one of Cantor’s main ideas in this way: There are many infinities, and thus there are many everythings. Now, it is possible to grasp this idea through a simple experiment:

I am not a mathematician (to say the least), but I still feel the heat of Cantor’s realizations. His work demonstrated a logical explanation to some discoveries that poets had made before him, thereby extending the poetic discoveries to the study of mathematics and the (albeit Sisyphean) ordering of chaos. Think, for example, of William Blake: To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower, Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour. Note the indefinite articles: “a World;” “a Heaven.” With this construction, we can picture a thousand of us scattered across the beaches of the planet, absorbed with the granules in our palms, each seeing a different world and a different heaven in our hands. How many worlds are there? At least as many as there are grains of sand. How many hours are in the day? Not 24, as we like to say; rather, there are infinite hours. It depends on how we look at it (to evoke a phrase that will also find mathematical justification in the eventual work of the profoundly bored patent clerk, Albert Einstein). Why does any of this matter for you? If, like me, you have experienced the devastating loss of loved ones and sunk to your knees with a single thought—Everything is ruined. All is lost—then the material, non-metaphorical existence of multiple everythings is, well, Everything. Personally, I experience multiple everythings (i.e., complete, disparate realities) at each moment of every day. In one reality, my two-year-old son Phalen runs around the apartment by himself and plays with blocks, and magnets, and balls, and books, and chalk, et. al. In another reality, my would/should-be-four-and-a-half-year-old son Finlay is here with him, functioning as an older brother to both enhance and obstruct Phalen’s fun. In another reality, Finlay isn’t here bodily but he is here as pure energy and infuses all matter with a buzz. In another reality, Finlay isn’t in this apartment at all because he has work to do elsewhere, and I feel this to be true in my bones. In another reality, I feel “nothing” and read this as a sign of his absence that hangs over my cavernous internal emptiness. All of these realities—and more—coincide in each moment of every day. When I allow the multiple everythings to develop in the darkroom of my mind, the words “Everything is Ruined” and “All is lost” lose their illusory power. Only one everything is ruined. In another everything, the ruins left behind in the shape of Finlay’s absence vibrate love into the universe like a beacon transmitting pure electricity. Only one all is lost. In another all, Finlay’s absence transmutes into a strange something that improves and empowers my parenting of his brother. This is not psychosis or derangement or poetic imagining. These alls all collaborate in the multiplicity of my Being. Returning to the starting point of these reflections (as a way of concluding), we notice that we have embarked on quite a journey. Nothing turns out to be a powerful something. Everything turns out to be the starting point of the many alls in which we participate at each moment of the day. Paired side by side, Everything and Nothing author an invitation to see beyond the surface of appearance and to journey into the Great Mystery. This episode brings us to the Raga Room, nestled in the highly charged environment of Black Mountain, North Carolina, where Will interviews Aditi Sethi, Jojo Silverman, and Greg Lathrop. Once each season, these musicians host a Ceremonial Grief Concert that harnesses the powers of collective grieving and music to hold space for the work of spiritual transformation in the wake of grief.

Listen Here: https://invitingabundance.net/to-grieve-podcast#Episode8 10/12/2018 0 Comments Write BrightlyWrite Brightly is now available!! I am extremely excited about this class. I've wanted to make something like this for years. I have stepped up my video-editing game and created a deep dive into the world of academic writing. I think you'll learn a lot.

|

AuthorWill Daddario is a historiographer, philosopher, and teacher. He currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed