|

6/18/2021 1 Comment Can We Talk About Grief?

My conversation on grief with Priya Jay for Fevered Sleep's "Can We Talk About Grief" series is available to watch on YouTube. Please listen if you are seeking a heartfelt dive into the multidimensional landscape of grief and healing.

1 Comment

9/14/2020 1 Comment Eulogy for Mary OverliePostmodern art practice has lost one of its most ardent proponents. Mary Overlie is dead at the age of 74.

It is fitting that a picture of her life and work will slowly come into focus through multiple viewpoints, as colleagues, students, and friends reveal glimpses of her giant contribution to contemporary performing arts. I offer my perspective here as a former student of Mary, her friend for 20 years, and an ongoing practitioner of the six viewpoints. The precise meaning of “viewpoints practitioner” is what I want to address in this short eulogy. Despite the global reach of the viewpoints, I suggest it is not a phrase that many people understand in the same way that Mary understood it. The primary reason for the confusion is twofold. On the one hand, there is the issue of Anne Bogart’s cooptation of the work. On the other hand, there is the anarchic horizontality of Mary’s teaching, which, while rigorous, caring, thorough, and artful, always resisted systematization and the rigid boundaries of rational coherence. To practice the viewpoints, for Mary, had less to do with composing works for theatre or dance and more to do with living life as art. Mary’s six viewpoints could be used to create showable experimental theatre and postmodern dance pieces, but this was merely one of its uses. More broadly, the six viewpoints was a breathing theoretical organism, a certain kind of performance philosophy that was equally available to welders, bridge painters, landscape architects, and casual pedestrians as it was to BFA and MFA artists. Bogart’s popularization of Mary’s work and Mary’s own presence as a teacher within one of the United States’s most innovative theatre conservatory programs may have given the viewpoints a semblance of knowability. But I don’t think anyone apart from Mary actually knew what it was and is. Our work, I believe, is to live into Mary’s teaching of the viewpoints so as to internalize the by-now all-too-familiar, yet deceptively deep, phrase “the performance of everyday life.” If we do that, then I think we become viewpoints practitioners. Nowhere was the living aspect of Mary’s viewpoints more palpable to me than in the late stages of her dying. Even after a grand mal seizure stunned her speech capacity, a panoply of medications coursed through her veins, a fatigued immune system had grown dim from a prolonged entanglement with cancer, and the contours of her own finitude began to show their seams, Mary’s herculean strength permitted her to speak on the phone with the same liquid perspicacity that I had always known. A couple weeks before her exit, I participated in a kind of duet with her that was not unlike an exercise in the Shape viewpoint. She presented various shapes in the form of thoughts and recollections to which I responded with my own shapes. She pondered, “Why am I still alive?” I asked, “Does it sound like Ornette Coleman?” She recalled of the jazz virtuoso, “He understood shape.” “The shape of jazz to come.” “Creativity.” “In pain?” “No pain.” “What would Barry Lopez say about it?” “The Arctic and Montana.” We went on like this for a while, touching on motherhood, the inside of time, dizziness, silence, crying, and other such textures. It was a completely normal conversation with Mary. But this time I was struck by her commitment to her own teaching. This was the viewpoints of dying. There she was, “standing in space,” aware of the fact that everything is moving, attuned to the Cunningham-like expression of the Cage-ian silence that buttresses all the buzzing, sensing the decay of her dura mater at a cellular level, calmly discoursing with a friend on creativity and the shape of things as the end of her life settled into view. The structures of Space, Shape, Time, Emotion, Movement, and Story were at play here in the grain of her voice and the correspondence between thoughts. I thought to myself: you don’t teach this. You learn this by going where you have to go. The viewpoints are a system for artfully going where we have to go, which is to say, going through life and through the door called death. Mary’s students will all have memories of times when the full molecular complexity of the universe became sensible during her classes. Two of my own memories stand out to me now. The first recalls a spontaneous trip to the Museum of Metropolitan Art. The class had decided to compose a viewpoints improvisation on the steps to the museum. We wanted to alert visitors and passers-by to the particular temporal dimension of entering a museum. It came to pass that all of us lined up on the stairs leading up to the front door, each person behind the other, creating something like a huge gnomon. The light from the sun cast our shadows onto the steps as we slowly, nearly imperceptibly, moved out of the line formation. That was it. The class felt straight away that something important had happened, though we couldn’t put it into words. We all sat down and fell into thought. More than a handful of pedestrians came up to ask us what that was. Were we artists? What were we making? Our only answer was, “a kind of time.” The other outing was also unplanned. It arose from an exercise on space. We wondered about the geometry of conversational distance and were curious to discover if such a thing was quantifiable, meaning could we, in fact, measure them all and then do something with the data? We departed the second-floor classroom of 721 Broadway, grabbed some hard hats, reflective vests, and measuring tapes from a tech storeroom in the building, and went outside. We stopped at every couple or group engaged in conversation between Tisch and Washington Square Park. We measured the distance between people. When we got to the fountain in the park, we climbed inside it and noticed that construction workers from a nearby building were waving at us from a distance of a couple hundred yards away. Somebody asked out loud, “Is this a conversation?” And then somebody else: “What counts as a conversation?” That question blew our minds and we realized that our measuring equipment was not calibrated to the task. We returned to the classroom and made dances built around the question, “What’s [the space of] a conversation?” These two memories reveal the subtle and deceptive depth of Mary’s work. Both classes were part of “advanced” viewpoints training, which meant that everyone in the class had dedicated the requisite 40+ hours to exploring each of the six viewpoints and were comfortable creating improvisations with those materials. Yet here we were engaged in rudimentary explorations of Time and Space. What appears so clearly to me now is that there is no such thing as advanced viewpoints because the irreducible complexity of the universe is present in the very first viewpoints class you ever take from Mary or from one of her students. Mary folded her life’s realizations into her work such that any encounter with the primary materials of the viewpoints launched the student-practitioner into the quantum realm of reality. Though we can now say that Mary is biologically dead, we can also say that she experienced many social deaths before her body stopped her working. She died every time people spoke of the viewpoints as Anne Bogart’s contribution to the world of theatre. She died every time people asked, “Mary Who?” She certainly died every time students engaged in the viewpoints without a willingness to confront the quantum realm of reality that attracted Mary’s attention since she was a young girl growing up in Montana. I think the only way she lived so long, despite the near persistent tolling of these social deaths, was that she crafted a pedagogical method that opened students’ eyes to the true depth of viewpoints work, thereby establishing a method for parrying the world’s slings and arrows. Her teaching was so precise that she helped students familiar with Bogart’s training to see the differences between the two sets of viewpoints straight away. Her teaching was so cunning that she was able not to answer the question “Mary Who?” but, rather, to accumulate greater mystery and awe, two of the key ingredients in pedagogical charisma. Her teaching was so smart that she could guide students effortlessly from walking around the room to probing the temporalities of their inner lifesystems in one snap of the fingers. Her teaching kept her alive, and I think her teaching is what we all must strive to understand as we continue on. That is to say, there is more to the six viewpoints than any of us think we know, and we would be doing the art world a favor by pursuing that “something more.” There are two aspects of this pursuit of which I am sure Mary would want us all to be aware. The first is intellectual, perhaps even philosophical. Shortly before she died, Mary told me that she hopes she can be reincarnated as a masterful, technically proficient dancer who never thinks with her/his/their head but only through the body. I said, “well, perhaps, but thank goodness that’s not how you came back this time around.” Within the practical work of the six viewpoints is a largely unexplored intellectual world that, if mapped, could change the way we teach the arts in primary, secondary, and higher education, not to mention the way we integrate the arts into other (seemingly) non-artistic fields. This intellectual component is underexplored, but certainly not a secret, as the first sentence of Moisés Kaufman’s jacket blurb to Standing in Space makes clear: “Mary Overlie is one of the greatest thinkers of the American Theatre.” A dancer? Yes. An institute builder who helped launch the Experimental Theatre Wing at ETW, co-founded Movement Research, the Danspace at St. Mark’s Church, and other international organizations? Definitely. But Mary was also a thinker, a theorist, and an intellectual, and that side of her work is something we must endeavor to understand in much greater detail. The second way in which I hope we pursue Mary’s legacy is through group experimentation. While words and language in the shapes of books and articles on her ideas are much needed, there is a bodily knowledge and movement-based thinking without which the viewpoints makes no sense at all. All students of the work understand what this means, but I wonder if we overlook the significance of experimenting with this kind of knowledge. To experiment in this sense means to engage in the work without a clear idea of what may come out of it. We ought to do this collectively, in classes, in-person, through Zoom, and in whatever way “collectivity” is possible. This is especially important to do now at a time when the meaning of “to gather” is changing greatly and when the instrumental use of education to obtain practical ends seems to predominate in all types of schooling. The viewpoints could become a method for teaching and learning generally and for showcasing the ways in which movement is itself a form of thought, one as deserving of attention as the critical capacity of individual “genius.” The timing of Mary’s biological death is, in other words, something for us to ponder. Occurring in such close proximity to the deaths of Kristin Linklater and Sally Banes, Mary’s death is a reminder that important work is frequently obscured by the shadows of “the great ones,” those who, for whatever series of reasons, have achieved legibility within the complex field of cultural production. Let us work harder to shine light on the work being done in those shadows. Next, given the tide change in education that is taking place now in the midst of the pandemic, we ought to consider seriously what place we are willing to make for the type of non-traditional pedagogy that Mary has created. How can experimentation continue to thrive in the arts education of the future? And, finally, what uncharted territories still remain within the phrase “the performance of everyday life?” Despite having had its heyday in the academe, this phrase continues to remind us that art and living are constantly entangled, which is also to say that art and dying are likewise entwined. Mary’s death can urge us to keep the borders of academic disciplines not only open to each other but also to the horizons of life and death in order to ensure that the work we do in the classroom speaks directly to the lives we lead on the streets. Finally, I’d like to relate one of Mary’s thoughts that she shared with me in her last weeks. During the last months or her life, despite her medical condition, Mary undertook a multi-week teaching tour through Europe and then a residency in Shanghai. During those trips, she earnestly discussed creating a bricks-and-mortar school for the study of the viewpoints, understood in all the senses (and more) that I’ve touched on here. Fascinatingly, her plan was to name this school something like, The Institute of Horizontality, a move that would have marked a profound letting go of the name “viewpoints” in order to grapple more directly with the nonhierarchical mode of living and thinking that Mary prized so much. I see in this act of letting go a model for how to continually deepen one’s engagement with art and also a challenge for all of us committed to the viewpoints. Each time we practice this work, which is to say, with each breath we take, we can sense the greater whole in which we all participate. To work through Mary’s viewpoints is to increase our aptitude of this participation. In this sense, it is possible to see death as more than the finite terminus of life’s long arc and, thus, to continue our work with Mary even if she is no longer here on this Earth to guide us. An edited version of this eulogy appears in PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 43.3 (Sept. 2020): 50–54. WILL DADDARIO is the author of Baroque, Venice, Theatre, Philosophy (Palgrave 2017), and co-editor of two anthologies: Adorno and Performance (with Karoline Gritzner, 2014) and Manifesto Now! Instructions for Performance, Philosophy, Politics (with Laura Cull Ó Maoilearca, 2013). He is co-editor of the Performance Philosophy Book Series and co-editor of the journal Performance Philosophy (performancephlosophy.org/journal). He currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina where he engages in grief work and continuing education services for local and international communities. 4/28/2020 1 Comment With grief, acceptance (ἡσυχία)A couple years ago, I wrote a follow-up to my essay on grief that meditated on the perplexing subject of “acceptance.” During a multi-day silent retreat in the mountains of Boone, North Carolina, I had an eye-opening realization about “acceptance,” which, up to that point, had appeared to me like a cruel and unrealizable fantasm, a point on a horizon I would always be able to see (through a perpetual squint) but never reach. The realization brought me closer to acceptance by, surprisingly, revealing the extent to which it was already upon me. In other words, I had at the retreat a leap in place facilitated by many hours of silent meditation and reflection. Recently, I decided to go back to this essay on acceptance and get it ready for publication. As a warm up for myself, I revisited the term “acceptance” in Ancient Greek to see what it could teach me. What follows is the lesson. Part 1: An Act of Translation The “acceptance” I’m grappling with is more than the simple reception of some idea or thing or state of mind. The “acceptance” in front of my eyes is the mythical at-peace-ness that is, ostensibly, the aim of the grieving process. To accept one’s grief is to be ok with it all, to understand one’s losses not as lacks or pure absences but, rather, as additions to the manifold self. The roadblocks to this realization are many, not least of which is the anger and sadness that produces wave after wave in the wake of loved ones’ deaths. More than that, the roadblocks are all somehow supposed to be metabolized by this mythical acceptance in an almost-magical transubstantiation of hardship into insight. Is there a word for this, a word that names something real and tangible? It turns out that this kind of “acceptance” does not have a direct equivalent in Ancient Greek. The verb λαμβάνω, meaning to take hold of or seize, for example, is too literal. Even its connotation of “understanding” is not quite right because of its mostly cognitive meaning, as in “I understand what Plato means when he says _____.” The most poetic word is λῆψις. Spoken or written in this way, to accept is to take one’s medicine. Acceptance is the cure for what ails us. The word also has a musical connotation: it is the setting of the key. In what register am I being asked to sing? Can I reach this pitch without straining, or do I need to train my voice? What kind of vocal regimen will allow me to reach the extraordinarily high pitch of Acceptance without hurting my voice over time? How can I sustain the pitch of Acceptance? Each of these questions opens into an ongoing musical practice that has as its end not an aesthetic beauty but a sustained cosmological consonance. Finally, this word also connotes the choice of poetic matter. In the context of my thoughts here, I might ask, what is the best way to tell the story of Acceptance? What story will adequately portray the humongous magnanimity of Acceptance’s act of giving? There is one more word that approaches the wide semantic range of “acceptance” I am exploring: δεχεσθαι or δέχομαι. Dio Chrysostom, in his 30th Discourse, relays the dying words of Charidemus, which shows why the word appeals to me: What has happened to me has happened in accordance with God’s will; and we should not consider anything that he brings to pass as harsh, nor bear it with repining: so wise men advise us, and Homer not least when he says that the gifts of the gods to man should not be spurned by man—rightly calling the acts of the gods ‘gifts,’ as being all good and done for a good purpose. As for me, this is my feeling, and I accept the decree of fate calmly, saying this, not at any ordinary time, but when that fate itself is present, and I see my end so near at hand. (Τὰ μὲν καθ᾿ ἡμᾶς οὕτω γέγονεν ὡς ἔδοξε τῷ θεῷ, χρὴ δὲ μηδὲν τῶν ὑπ᾿ ἐκείνου γιγνομένων χαλεπὸν ἡγεῖσθαι μηδὲ δυσχερῶς φέρειν, ὡς παραινοῦσιν ἄλλοι τε σοφοὶ καὶ οὐχ ἥκιστα Ὅμηρος, λέγων μηδαμῇ ἀπόβλητα εἶναι ἀνθρώποις τὰ θεῶν δῶρα, καλῶς ὀνομάζων δῶρα τὰ ἔργα τῶν θεῶν, ὡς ἅπαντα ἀγαθὰ ὄντα καὶ ἐπ᾿ ἀγαθῷ 9γιγνόμενα. ἐγὼ μὲν οὖν οὕτω φρονῶ καὶ δέχομαι πρᾴως τὴν πεπρωμένην, οὐκ ἐν ἑτέρῳ καιρῷ ταῦτα λέγων, ἀλλὰ παρούσης τε αὐτῆς καὶ τὴν τελευτὴν ὁρῶν οὕτως ἐγγύθεν.) This particular kind of acceptance is, first, a mode of mental reception, but it is, moreover, a full “taking upon oneself” of one’s own fate. The “gift” of the gods is the perfect primer for the acceptance yoked to grief because it is a gift you cannot, are simply unable to, refuse. Even if you don’t want it, the gift only exists as something already given, and no mental or physical acrobatics can make it ungiven. In fact, we humans accept this gift in the same gesture as it is given, or else we suffer through a tragic farce of attempting to shake off something already part of ourselves. This is especially the case with our own death, which is given unto us as soon as we are conceived. Ultimately, however, even δέχομαι stops short of the acceptance I seek. I decided instead to follow a path marked in the dictionary by the word “acquiesce.” My act of translation senses harmony in the “quiet” of this verb. But “acquiesce,” with its French sensibility of “to yield or agree to; to be at rest,” leads back ultimately to Latin and, therefore, doesn’t have a Greek cognate. As such, the path forces me to leap toward something less common, a word near to “accept” but more capacious and mysterious. Part 2: To be at peace My act of translation leads me, eventually, to the enigmatic word ἡσυχία. The word’s mysterious quality comes from the shadow cast upon it by Christianity. That is, looking back from the present toward the classical emergence of this word requires us to pass through its employment in Biblical verse, and specifically its usage in Orthodox Eastern Christianity where it refers to an inner quiet that leads to a oneness with God. Thinking historiographically, it seems likely that Christians first encountered ἡσυχία through pluralistic scholars like the Hellenstic Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria. In Philo’s On Flight and Finding, for example, we see the following: To these inquiries the other gives the only right answer, “God will see for Himself” [...] For it is by His taking thought for them that the mind apprehends, and sight sees, and every sense perceives. As for the words [i.e., idiomatic expression] “A ram is found held fast,” this is reason keeping quiet and in suspense. For the best offering is quietness and suspense of judgement, in matters that absolutely lack proofs. The only word we may say is this, “God will see.” (ταῦτα πυνθανομένῳ δεόντως ἀποκρίνεται· “ὁ θεὸς ὄψεται ἑαυτῷ”· θεοῦ γὰρ ἔργον ἴδιον τὸ τρίτον. ἐπιφροσύνῃ γὰρ αὐτοῦ ὁ μὲν νοῦς καταλαμβάνει, ἡ δ᾿ ὅρασις ὁρᾷ καὶ πᾶσα αἴσθησις αἰσθάνεται.“κριὸς δ᾿ εὑρίσκεται κατεχόμενος,” τουτέστι λόγος ἡσυχάζων καὶ ἐπέχων. ἄριστον γὰρ ἱερεῖον ἡσυχία καὶ ἐποχὴ περὶ ὧν πάντως οὔκ εἰσι πίστεις. ῥητὸν γὰρ μόνον τοῦτο “ὁ θεὸς ὄψεται [...]”) If we seek to understand how so many Ancient Greek philosophical ideas wound up in early Christian thinking, we could investigate points of contact between figures like Philo and, say, Paul the Apostle. The historiographical challenge requires seeing through Philo back into spaces where ἡσυχία acted in its Ancient Greek clothing, so to speak. To do that, we have to keep digging into texts by the likes of Plato and Pindar whose thinking predates the Christian episteme. For example, in Book IX of Plato's Republic we find Socrates asking questions about pain and pleasure. He wonders whether, for people in pain, the relief (ἡσυχία) of pain is more desirable than the feeling of wellness. In usual fashion, Socrates’ interlocutor is quick to agree with the great philosopher when he says, “And you notice, I think, when people get into many other similar situations in which, when they’re in pain, they praise not the feeling of joy but not being in pain and the relief from that sort of thing as the most pleasant sensation.” “Yes, this is perhaps what then becomes pleasant and desirable: the relief.” For my inquiry, this notion of relief is central to acceptance since, after all, the accepting of one’s grief ought to bring not the erasure of the conditions that brought the pain to be but relief of that pain’s sting. “Relief” is absent from the translations of acceptance I mentioned above. Another resonant morsel sings out through Pindar who, in his 8th Pythian Ode, reminds us that the noun ἡσυχία is derived from Ἡσυχία (same pronunciation), the daughter of Dike, goddess of Justice. Her name is synonymous with Peace, specifically peace within the polis (city). Justice presides over the political practice and philosophy of a place and Peace presides over the place itself as a kind of adjunct to Justice. When Justice is present, so too will be Peace. My train of thought leads from acceptance to ἡσυχία and moves through a series of stations. First, acceptance is most certainly a state of mind, a kind of mental reception that allows one to understand the events that have befallen them. But this cognitive understanding is only the first blush of acceptance. (Think, for instance, of times when you say that you know something to be true but you don’t yet feel it. Here, the mind grasps some truth but the body has not yet fully metabolized it.) Mental acceptance must be accompanied with a full-bodied acceptance of the gift of one’s fate. It seems to be the case, however, at least in my experience, that acceptance of this gift is a perpetually repeating action. Each moment asks of acceptance insofar as each moment of life is a gift given. The consequence of this is something like an acceptance seizure that shudders through the body and can only be calmed by a kind of inner peace. Attainment of this peace begins with an inner quieting (acquiescence), and the quiet allows the self to sense the great expanse of the self (something usually muted or occluded by the ego and/or traumatic memories). Here we reach the stations of Pindar and Plato since inner quiet is truly a relief and Peace, and this Peace is offspring of Justice insofar as the sense of self that results from ἡσυχία is tantamount to finding balance. Here we find another way of thinking about the “stage” of acceptance. The so-called stages of grief are not thresholds through which we pass but are, rather, environments in which we fully immerse ourselves. The environment of acceptance is everywhere a space of peace and calm. Plato’s Timaeus contains a discussion of the “inner fire” going away when sleep befalls us. A quiet ensues within the mind and body right before deep sleep. Thus, in the moment of falling asleep we sense the environment of Peace that marks the domain of acceptance. In his “Twentieth Discourse: Retirement,” Dio Chysostom speaks of the silence and quiet needed by the sick to fully recover from illness, and this peaceful environment is also the space of acceptance where those who ail become receptive to their state. All of this is to say, the acceptance yoked to grief is an environment, but—and here’s the mind-blowing thing—we’re always already in this environment. Delusion and temporary blindness distract us from the fact that we are always already dwelling within this Peace. If we seek acceptance, then we already walk in the wrong direction since no seeking is required. To seek is to assume not to dwell. No seeking. Only being. A being-with oneself and one’s grief. This revelation stops any attempt at moving through grief’s stages and convinces us to fall quiet. This blog entry is a portion of a multi-part sequence of posts dedicated to the Ancient Greek language. You can read the rest by following these links:

4/20/2020 0 Comments What of No?In anticipation of the 2021 Performance Philosophy conference, I've been thinking about "problems" in the sense that Deleuze discussed them. I particularly like Bourassa's parsing of the term in the book Deleuze and American Literature:

"Problems, far more than solutions, open our eyes. It is said that every solution is worthy of its problems and that every problem gets the answer that it merits. So we can talk about good and bad problems, problems that are more or less worthy. And this is truly the challenge of thinking. Not to get the 'correct' answers, but to formulate the worthy problems, problems that carry their answers with them in the clarity and rightness of their form. [...] The difference between a bad problem and a good one is that the bad problem demands a solution that will quickly be recognized and validated. When we read the essay that portentously comes to the same conclusion as the last dozen essays of its kind, we are in the presence of a worn-out problems. A good problem is one that changes our vision, makes new things visible, breaks up the previous divisions, and installs new ones (which may themselves be replaced). The good problem is often the articulation of a mystery that has not been voiced, and in the setting out of the mystery, much comes to us, not as answers, but as singular points of the question we have posed" (2009, 195; this appears in the conclusion where the problem being put forth is that of the Nonhuman)." In this sense, a Performance Philosophy problem would be one of the mysteries that have evolved within the seams of the organization since its emergence in 2013. I'm interested in the problem of "No," and I'd like to explore it along the following lines:

4/11/2020 0 Comments Notes on acceptance (ἡσυχία)The Ancient Greek word for the type of acceptance I've been thinking about is most closely related to "acquiescence." [I'll have to explain why I think that word is best.] But that word is from Latin, not Greek, so I started looking at the Greek words for "quiet" and "to become quiet."

I find: ἡσυχία, rest of quiet personified; to be at peace or rest In the Loeb Classics, it shows up in a number of places, but most interestingly in Pindar's 8th Pythian Ode where it is offered as a proper name: Ἡσυχία. The translator flags it for footnoting: "Hesychia, peace within the polis, is the daughter of Justice."

“And you notice, I think, when people get into many other similar situations in which, when they’re in pain, they praise not the feeling of joy but not being in pain and the relief from that sort of thing as the most pleasant sensation.” “Yes, this is perhaps what then becomes pleasant and desirable: the relief,” he said. Robert A. Bauslaugh links the term to "neutrality," as in political inaction due to policy. Other sources:

(Full version coming soon)

Nurse:

Nursing:

Attending:

Secondary sources Yannicopoulos, A. V. (1985). The pedagogue in antiquity. British Journal of Educational Studies, 33(2), 173–179. doi:10.1080/00071005.1985.9973708

Christian Laes, “Pedagogues in Greek Inscriptions in Hellenistic and Roman Antiquity,” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bd. 171 (2009): 113-122.

I have a frictious relationship with repetition. On the one hand, I don’t believe that anything ever repeats, not really, at least not in the strict sense of a “repetition of the same.” For example: I I I I I I I I. This is not the repetition of the same I. Each I is different. Each occupies a distinct space and has resulted from a distinct pressing of my computer’s keyboard. In casual conversation, one could easily suggest that I have repeated I. But when I really think about it, I don’t see a single I repeated. I see I and I and I and I, always new.

On the other hand, my body seems to feel the return of habitual action, specifically habitual actions that trouble me. The air seems to thicken each morning at 7am when my three-year-old bolts out of bed to start a new day. My body drags itself to an upright position so as to follow and hesitates because of a deep uneasiness about doing this again, of trying to get energy again, of repeating the struggle of parenting. I could possibly describe this as a “continuation” of parenting, instead of a “repetition,” except that there is something very Groundhog’s Day about it. Same with the non-linear path of potty training: poop, again! In this scenario, it doesn’t feel like new poop. It feels like I’m re-living the totality of the “training” process. At the other end of the continuum, where this repetition feels most invasive, I encounter trauma, which is the epitome of this bodily sensation of repetition: I, in the present moment, feel again a series of affronting and unwanted bodily reactions that I have experienced before. This is related to the idea of nomos that I wrote about last time, the habit of experience that instantiates itself through (ostensibly) repeated action. I have a frictious relationship with repetition. Does it exist as a natural phenomenon of life, or am I the one who fabricates it? To answer this question, I have, for years, explored the topic of repetition in theatre and performance studies. Each time one performs (any habitual activity) or each time an actor steps onstage to enact a part in a pre-designed performance, what precisely is happening? Do we repeat our actions, or is each time a totally new experience? The most intriguing treatment of these questions, however, appears not in theatre and performance scholarship but in philosophy and psychoanalysis. Gilles Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition and Jacques Lacan’s re-workings of Sigmund Freud’s thoughts on repeated (neurotic and desirous) behavior are texts I return to, repeatedly (?). >>READ MORE<< 1/14/2020 1 Comment To repeat (yet again)Notes for forthcoming entry on repetition:

Repeat and Repetition

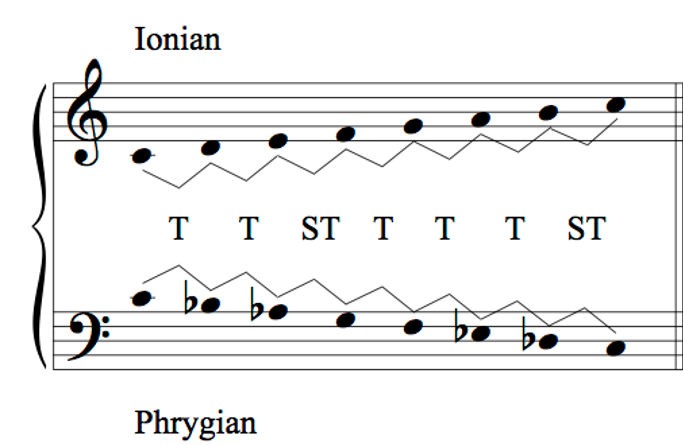

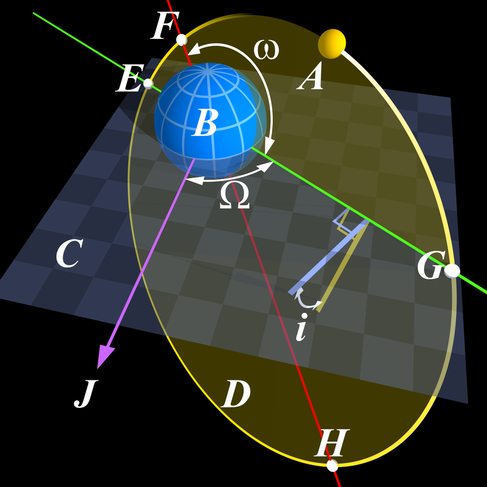

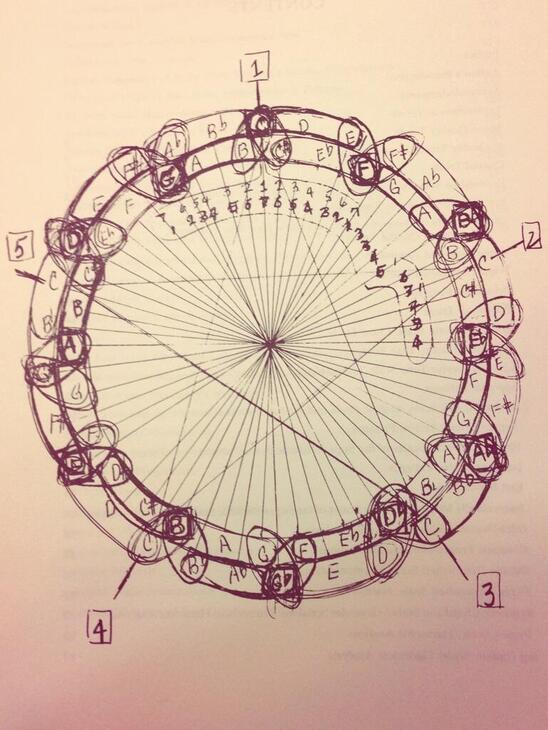

I recently purchased a subscription to the Loeb Classics Online Library. To encourage my use of this amazing resource, I am starting a blog series called "Classical Bellyflop." The name comes from the feeling of leaping or diving into the classical texts curated in that library. Since my knowledge of Ancient Greek and Latin is pretty basic, however, any dive would scarcely resemble something pretty; not even a cannonball or a jack-knife would serve as an adequate comparison. No, when I dive into Ancient Greece I most certainly bellyflop. The text-water slaps me with as much force as my dive carries with it. The discoveries I make in the text are usually eye-opening and sometimes startling, similar to the surprisingly painful sensation of breaking the water’s surface. In these blog entries, I am confidently admitting my ugly bellyflop into these classical texts. Combined with definitions sourced through the Liddell and Scott online dictionary, these forays into the Loeb Classical Library will chronicle my flops and present them as lessons. Why lessons? Why share these bellyflops? I am convinced that words are used too carelessly today. The rich histories packed into each and every word of the English language are hardly ever examined. As a teacher and a writer, I feel called to publicize some of these histories and the lessons that I myself learn every time I unpack the language that I use. Additionally, despite the foreignness of the Ancient Greek alphabet, the English language relies on Ancient Greek words to a great extent. Knowing a bit about this reliance helps us to become more astute readers and critical thinkers. This, at least, is my hope. The first word I am exploring is νόμος (nomos). You have likely encountered this word many times, though it is usually nested within a larger word, such as “astronomy,” “autonomy,” and “antinomial.” The most common definition of “nomos” is “that which is in habitual practice, use or possession,” “use, custom,” and, more generally, “law.” Thus, “astronomy” is the law or habit of the stars. “Autonomy” means to govern the self (auto = self). “Antinomial” is formed by fusing “against” (anti) and “nomos” (law) and means “the rejection of law.” As I’ll show in what follows, this usual definition is accompanied by a now rare meaning linked to the production of music in Ancient Greece. Since music, mathematics, and philosophy were so intimately related for the Greeks, this forgotten definition of nomos helps us peer into the connection between order, the frequency of sound, and the workings of both human society and the wider universe. I discovered this new-old definition of νόμος while writing a book with my friend and collaborator, Matthew Goulish, which maps the contours of the astonishing poetry, drama, and philosophy of Jay Wright. While reading Wright’s most recent book of poetry, The Prime Anniversary (2019), I encountered this verse: That periodic bouncing between mirror points might define the note’s order in the scale. Custom could determine all that the spent soul might fathom, make of it a blue galaxy that disappoints. Consider a slow dance about an axis, dust in an elliptical field. Now Emily must go mad with her math, and take these errors in trust. You’ll have to wait for the book to hear our fullest interpretation of stanzas like this one. For now, let me draw your attention to the second line where Wright ends the first sentence and begins another: “[…] the note’s order in the scale. Custom”. It seems that Wright is aware of the familiar and less-than-common definitions of νόμος. He has united two sentences that each summon one of these definitions. “Custom” hearkens to the traditional meaning, and the discussion of a note’s order in a scale calls to mind the following: “melody [...] a type of early melody created by Terpander for the lyre as an accompaniment to Epic texts.” The Prime Anniversary is dedicated to exploring ancient philosophical ideas in verse, as did the pre-Socratic philosophers. This fact helped me tune into the subtle reference that one could easily miss while trying to figure out what precisely Wright is talking about here. To give a brief peek into the complex working of this passage, I’ll widen my scope to the entirety of the first sentence: “That periodic bouncing between mirror points / might define the note’s order in the scale.” A “mirror scale,” or “mirror mode,” which comes to mind because of Wright’s word choice, is a musical phenomenon that reveals the type of “distance” between notes that so interested Ancient Greek philosophers. Arthur Fox helps us understand what’s going on in one of his blog entries: Try reversing or “mirroring” the order of intervals in any given scale. Reversing the order of intervals in a palindromic scale will produce the same scale. Otherwise, we will end up with a new ‘mirror scale‘ that is on the opposite side of the brightness/darkness spectrum. So, for example, intervals between the scale degrees of the Major (Ionian) scale are as follows: T – T – ST – T – T – T – ST. If we mirror these degrees, we get the Phrygian mode. For the Ancient Greeks, geometrical relations such as those revealed through the realization of mirror scales hinted at an underlying structural code to the cosmos. Philosophers such as Pythagoras, and even more staid ones like Plato, sought to understand whether the discernment of those underlying codes in nature could translate into a harmonious political situation among humans. If so, then the law of the land (nomos) might be developed from a deep understanding of musical harmony and the placement of notes in a scale (nomos). In fact, despite his protestations against music and its ability to mislead the soul, Plato seems to hint at the benefit of such realizations in his dialogues Laws and Statesman. Wright, too, senses resonance between the mathematics of harmonious musical relations and the order of the universe, which is why this stanza moves on to discuss the phenomenon of the Blue Galaxy and elliptical orbits. Unlike Plato, however, whose philosophical systems seem to conserve a top-down governmental structure in human society, Wright’s poetry brings some dissonant dissidence. His fusion of sources challenges us to unite cultures and ideas that most people keep separated into categories like “Western,” “African,” “Musicology,” and “Philosophy.” By dismissing the historically developed separation of various modes of thought and cultural production, Wright allows us to think up new combinations. Or, rather, he helps us revisit old unities that provided glimpses of the active Oneness to the universe. If you think about the geometry of music long enough, you’ll start to understand why so many musicians find spiritual power in their art. A prime example is John Coltrane whose famous diagram of the circle of fifths hints at his dual role as mathematician.

When we listen to Coltrane and dwell on images like this, we find another example of the two-fold definition of nomos, much like in Jay Wright’s poem. At stake in Coltrane’s music is the possibility of re-ordering the habits of society through coming up with heretofore-unheard-of orders of notes, as if thinking up new musical formations will bring about a social revolution. Nomos evokes nomos. Play the old standards, things stay the same. Blow off the roof and change blows through. At this point, it seems important to point out that, in a relatively limited number of steps, I have maneuvered from a dictionary of Ancient Greek words to a theory of political revolution embedded within a jazz musician’s sound. The Loeb Classical Library sent me back to A Love Supreme. What’s important here is not that I’ve discovered some new connection between seemingly disparate human artefacts. Rather, I’ve discovered something that was already embedded in the word “law” or “custom,” a type of knowledge that was released through poetic verse. Is there, perhaps, a methodology here that we can put to repeated use? Begin with poetry. Peer deep into the structure and words of the poetic verse. Unpack the history of the terms and listen to what that history has to say. Through listening, rediscover truths that have been forgotten or intentionally pushed aside, and then put those truths into action in order to bring about change. |

AuthorWill Daddario is a historiographer, philosopher, and teacher. He currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed