|

1/14/2020 1 Comment To repeat (yet again)Notes for forthcoming entry on repetition:

Repeat and Repetition

1 Comment

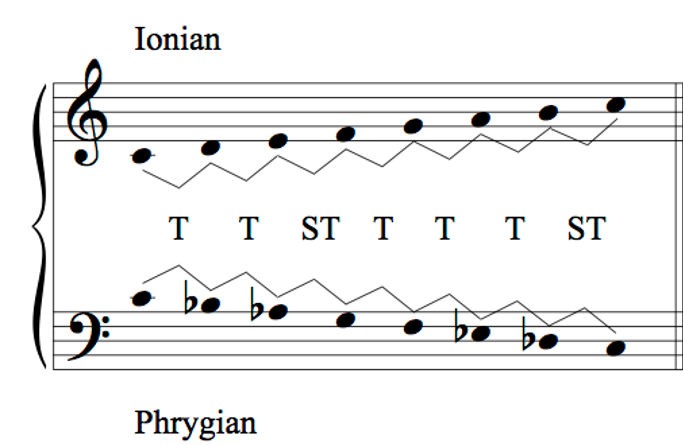

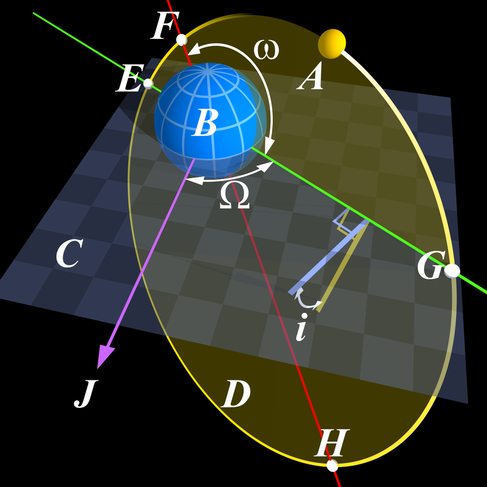

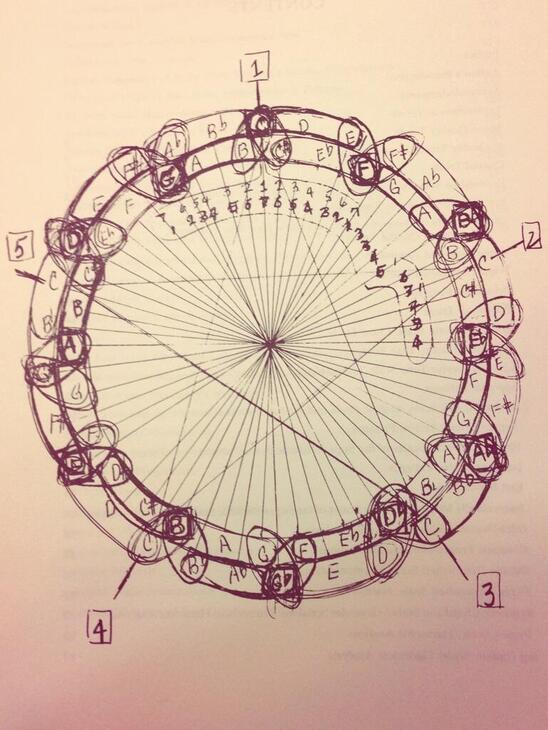

I recently purchased a subscription to the Loeb Classics Online Library. To encourage my use of this amazing resource, I am starting a blog series called "Classical Bellyflop." The name comes from the feeling of leaping or diving into the classical texts curated in that library. Since my knowledge of Ancient Greek and Latin is pretty basic, however, any dive would scarcely resemble something pretty; not even a cannonball or a jack-knife would serve as an adequate comparison. No, when I dive into Ancient Greece I most certainly bellyflop. The text-water slaps me with as much force as my dive carries with it. The discoveries I make in the text are usually eye-opening and sometimes startling, similar to the surprisingly painful sensation of breaking the water’s surface. In these blog entries, I am confidently admitting my ugly bellyflop into these classical texts. Combined with definitions sourced through the Liddell and Scott online dictionary, these forays into the Loeb Classical Library will chronicle my flops and present them as lessons. Why lessons? Why share these bellyflops? I am convinced that words are used too carelessly today. The rich histories packed into each and every word of the English language are hardly ever examined. As a teacher and a writer, I feel called to publicize some of these histories and the lessons that I myself learn every time I unpack the language that I use. Additionally, despite the foreignness of the Ancient Greek alphabet, the English language relies on Ancient Greek words to a great extent. Knowing a bit about this reliance helps us to become more astute readers and critical thinkers. This, at least, is my hope. The first word I am exploring is νόμος (nomos). You have likely encountered this word many times, though it is usually nested within a larger word, such as “astronomy,” “autonomy,” and “antinomial.” The most common definition of “nomos” is “that which is in habitual practice, use or possession,” “use, custom,” and, more generally, “law.” Thus, “astronomy” is the law or habit of the stars. “Autonomy” means to govern the self (auto = self). “Antinomial” is formed by fusing “against” (anti) and “nomos” (law) and means “the rejection of law.” As I’ll show in what follows, this usual definition is accompanied by a now rare meaning linked to the production of music in Ancient Greece. Since music, mathematics, and philosophy were so intimately related for the Greeks, this forgotten definition of nomos helps us peer into the connection between order, the frequency of sound, and the workings of both human society and the wider universe. I discovered this new-old definition of νόμος while writing a book with my friend and collaborator, Matthew Goulish, which maps the contours of the astonishing poetry, drama, and philosophy of Jay Wright. While reading Wright’s most recent book of poetry, The Prime Anniversary (2019), I encountered this verse: That periodic bouncing between mirror points might define the note’s order in the scale. Custom could determine all that the spent soul might fathom, make of it a blue galaxy that disappoints. Consider a slow dance about an axis, dust in an elliptical field. Now Emily must go mad with her math, and take these errors in trust. You’ll have to wait for the book to hear our fullest interpretation of stanzas like this one. For now, let me draw your attention to the second line where Wright ends the first sentence and begins another: “[…] the note’s order in the scale. Custom”. It seems that Wright is aware of the familiar and less-than-common definitions of νόμος. He has united two sentences that each summon one of these definitions. “Custom” hearkens to the traditional meaning, and the discussion of a note’s order in a scale calls to mind the following: “melody [...] a type of early melody created by Terpander for the lyre as an accompaniment to Epic texts.” The Prime Anniversary is dedicated to exploring ancient philosophical ideas in verse, as did the pre-Socratic philosophers. This fact helped me tune into the subtle reference that one could easily miss while trying to figure out what precisely Wright is talking about here. To give a brief peek into the complex working of this passage, I’ll widen my scope to the entirety of the first sentence: “That periodic bouncing between mirror points / might define the note’s order in the scale.” A “mirror scale,” or “mirror mode,” which comes to mind because of Wright’s word choice, is a musical phenomenon that reveals the type of “distance” between notes that so interested Ancient Greek philosophers. Arthur Fox helps us understand what’s going on in one of his blog entries: Try reversing or “mirroring” the order of intervals in any given scale. Reversing the order of intervals in a palindromic scale will produce the same scale. Otherwise, we will end up with a new ‘mirror scale‘ that is on the opposite side of the brightness/darkness spectrum. So, for example, intervals between the scale degrees of the Major (Ionian) scale are as follows: T – T – ST – T – T – T – ST. If we mirror these degrees, we get the Phrygian mode. For the Ancient Greeks, geometrical relations such as those revealed through the realization of mirror scales hinted at an underlying structural code to the cosmos. Philosophers such as Pythagoras, and even more staid ones like Plato, sought to understand whether the discernment of those underlying codes in nature could translate into a harmonious political situation among humans. If so, then the law of the land (nomos) might be developed from a deep understanding of musical harmony and the placement of notes in a scale (nomos). In fact, despite his protestations against music and its ability to mislead the soul, Plato seems to hint at the benefit of such realizations in his dialogues Laws and Statesman. Wright, too, senses resonance between the mathematics of harmonious musical relations and the order of the universe, which is why this stanza moves on to discuss the phenomenon of the Blue Galaxy and elliptical orbits. Unlike Plato, however, whose philosophical systems seem to conserve a top-down governmental structure in human society, Wright’s poetry brings some dissonant dissidence. His fusion of sources challenges us to unite cultures and ideas that most people keep separated into categories like “Western,” “African,” “Musicology,” and “Philosophy.” By dismissing the historically developed separation of various modes of thought and cultural production, Wright allows us to think up new combinations. Or, rather, he helps us revisit old unities that provided glimpses of the active Oneness to the universe. If you think about the geometry of music long enough, you’ll start to understand why so many musicians find spiritual power in their art. A prime example is John Coltrane whose famous diagram of the circle of fifths hints at his dual role as mathematician.

When we listen to Coltrane and dwell on images like this, we find another example of the two-fold definition of nomos, much like in Jay Wright’s poem. At stake in Coltrane’s music is the possibility of re-ordering the habits of society through coming up with heretofore-unheard-of orders of notes, as if thinking up new musical formations will bring about a social revolution. Nomos evokes nomos. Play the old standards, things stay the same. Blow off the roof and change blows through. At this point, it seems important to point out that, in a relatively limited number of steps, I have maneuvered from a dictionary of Ancient Greek words to a theory of political revolution embedded within a jazz musician’s sound. The Loeb Classical Library sent me back to A Love Supreme. What’s important here is not that I’ve discovered some new connection between seemingly disparate human artefacts. Rather, I’ve discovered something that was already embedded in the word “law” or “custom,” a type of knowledge that was released through poetic verse. Is there, perhaps, a methodology here that we can put to repeated use? Begin with poetry. Peer deep into the structure and words of the poetic verse. Unpack the history of the terms and listen to what that history has to say. Through listening, rediscover truths that have been forgotten or intentionally pushed aside, and then put those truths into action in order to bring about change. |

AuthorWill Daddario is a historiographer, philosopher, and teacher. He currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed