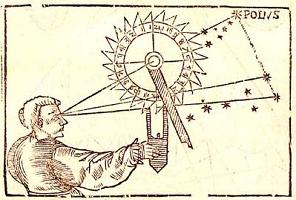

One of our primary offerings at Inviting Abundance is something we call “wayfinding.” In its most general sense, wayfinding is the system by which all living beings orientate themselves in space and navigate their surroundings. When linked to the processes of grieving and education, wayfinding names the methods we use to thrive amid life’s challenges, from living with the death of loved ones to encountering the bewildering complexity of being human. In this post, I (Will) want to analyze and reflect upon a strange phrase that first drew me to the concept of wayfinding. This phrase is “dead reckoning.”In order to live and thrive while grieving for the deaths of my son, father, stepfather, and friends, I have to reckon with death: How do these people’s deaths affect my ability to navigate through the social world? How do their deaths change my relation to life, generally? Is death really an end, or is it more like a threshold that opens onto a new beginning? By asking these philosophical questions, I feel that I am arranging the deaths of my family members into an order, one that acts like a trail capable of leading me in a specific direction. Here, the histories of the word “reckon” come into view: “to explain, relate, recount, arrange in order” as well as “to settle accounts.” Dead reckoning is a helpful term to know when facing life’s ultimate limit. The term, however, is more common in the world of nautical navigation. Historically, sailors would determine their current position by calculating their previous position (such as port of embarkation) and their ships’ speed over a specific duration. With the knowledge of their current location, sailors could then adjust their heading and navigate around known obstacles. The process of finding one’s location at sea was called dead reckoning. As a philosopher, I’m drawn to the function of the “present position” in this nautical wayfinding practice. Sailors and grievers alike need to understand their present place in order to know where they’re going. But knowledge of “where one is” comes about only after making some analytical/mathematical calculations. We can’t know where we are unless we know where we’ve been and where we want to go. On the sea, past and future position is a matter of course; on the open seas of grief, by distinction, past and future locations aren’t so easy to ascertain, and thus knowledge of “where one is” in the world requires more intuitive calculations. Applied to the more philosophical kind of wayfinding, dead reckoning becomes a useful but extraordinarily difficult process for healing. In this task of healing, we come upon a specific dimension of the word “dead”: “of water, ‘still, standing,’ from Proto-Germanic *daudaz.” Grief drops us in the still waters of the deep ocean of the soul. Without wind or current, these waters keep us in place and force us to comprehend the depth and expanse of the waters in which we are floating. I think of this dead water as the doldrums, a word that surfaces in Book IV of Homer’s Odyssey and refers to windless ocean travel, the worst kind of situation for a sailor trying to make his way home. The only way to summon the wind is to make an offering to the right spirit (Proteus) and/or god (Poseidon). Without faith in such spirits, people are left to float until chance intervenes. Even with faith and certainty in the spirit world, helping hands from beyond arrive on their own schedule, and waiting for help can be just as painful as the original traumatic experience that left us stranded in the first place. But in that still water where no wind blows, an opportunity also presents itself. It is there that we have cause to think and talk to ourselves. The gnawing boredom we feel during the incessant waiting amid grief actually sparks the imagination and forces a necessary encounter with the self. Nietzsche referred to this “boredom” as “that disagreeable ‘lull’ of the soul that precedes a happy voyage and cheerful winds.” It is a disposition common among artists who actually need this boredom brought on by still waters in order to ruminate, connive, and create. Most importantly, the doldrums bring about a stillness of soul that helps us individually to reckon with ourselves, as if to say, “Ok. Fine. What is this all about then? What am I doing here? What is here?” Philosophical wayfinding starts “here,” in the dead reckoning compelled by the trials of grief and sorrow. This “here” is also the “now” that Buddhists speak of when challenging us to remain present. Pema Chödrön helpfully reminds us that there is no escape from this now because there is nothing other than right now. The wisdom of no escape leads to sharper vision of one’s current circumstance, and it is this vision that Joanne and I have discovered over the last several years. We now see in the present moment a faint channel leading off to the horizon, and we set our compass to its heading everyday. Our son Finlay acts as our guide to keep us on course. We think of him as our wind spirit who fills our sails. The agony of impatience and the length of the journey still lead to despair and moments of anguish, but we know we’re not lost. We are, to the contrary, on the path to what we call “living grieving,” which is a mode of living life open to the elements, receptive to whomever we meet along the journey, and directed by the strengths we’ve honed over our many years on this planet.

1 Comment

|

AuthorWill Daddario is a historiographer, philosopher, and teacher. He currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed